For some time I have been going to a men’s group. Imagine the scene, men talking about the relationships in their lives. Inevitably the conversations goes into the topic of fathers and sons. Even though the group has been meeting for a while, at the start of this important topic people are still a bit guarded with their words, but once it gets rolling you cannot get them to stop. The first man opens up that his father was a failure, his whole life has been defined by his efforts to be successful in ways that this father missed the mark. While he has stumbled along the way, this drive has helped him build up a globally recognized brand. He is a star. Moved by this story, the second man shares that his father was so completely devoted to his work and pleasing his boss that he sacrificed their relationship. This story resonates with Harry Chapin‘s classic Cat’s in the Cradle. This cuts deep for me. I know I cry every time I hear that song. It is clear to me that this second man is blinded by the perceived neglect of his father. The third man shares his resentment of his father for loving his brother more then him. Why did he have to pick a favorite? No matter what he did, he could not get his father to value him for his own gifts. There was never a way for him to be worthy of his father’s love. Things got so bad that he actually ran away. He too found success, but in the end all he really wanted was validation from his father. He was like Citizen Kane searching for Rosebud as a symbol of the pure love of his parents. The stories go on, but you get the point. There is a thick and often challenging bond between fathers and sons.

While these all seem like caricatures, there are elements of each of these stories that we can relate to in our own lives. We all have issues with our parents. I have been thinking about my relationship with my father this week. It would have been his 88th birthday.

I was thinking about these issues as we transition from Noah, this week’s Torah portion, to Lech Lecha, next week’s portion. Next week we read about the dramatic launch of our people. Our nation’s journey begins with God instructing Avram (soon to become Avraham) to leave his birthplace and set out to start a new people in a new land. What a novel concept? A people collected by common belief as opposed to an accident of birth place. But if we were paying attention to the end Noah we would have seen that the destination for Avram’s travel was not new at all. We learn here that Terah, Avram’s father, had set out with his family toward the land of Canaan, but never got there. Here we at the end of Noah we read:

Terah took his son Avram, his grandson Lot the son of Haran, and his daughter-in-law Sarai, the wife of his son Avram, and they set out together from Ur of the Chaldeans for the land of Canaan; but when they had come as far as Haran, they settled there. The days of Terah came to 205 years; and Terah died in Haran. ( Genesis 11:31-32)

It seems that Avram was more successful than his father in terms of getting to the land of Canaan, but as we will see next week Avram is as unsuccessful as his father in terms of staying there. Avram left the land of his divine quest almost as soon as he got there. But maybe Avram’s ultimate success was not despite his father’s failure, but because of it. Maybe Terah’s failure was the drive for his son.

I was thinking about this recently when praying the first blessing of the Amidah. There we pray:

Blessed are You, Lord our God and God of our fathers – v’elohei avoteinu. God of Avraham, God of Yitzhak, and God of Yakov.

Why do we pray in the name of the God of each and everyone of of the forefathers? What does it say God three times? This is a question I have pondered for most of my life. I always assumed that we were looking at these three founding father’s unique relationship with God as a model for how we might approach God at the start of our prayer.

While I still think that is important, recently I got to wonder about the extra language of calling God “the God of our fathers”, this seems unnecessary seeing that we go on to spell that out. Imagine that the “fathers” in question is an invitation to explore how Avraham, Yitzhak, and Yakov each saw their relationship with God as defined by their relationship with their respective fathers. None of them had such a great relationship. This seems significant. How much of all of us define our relationship with God despite or to spite our relationships with our parents?

The theological frame of the relationship between fathers and sons came to light for me years ago when I went through and listened to many essays from This I Believe. This I Believe is an international organization engaging people in writing and sharing essays describing the core values that guide their daily lives. One of the pieces that has stuck with me was by John W. Fountain. He is a professor of journalism at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His essay The God Who Embraced Me When Daddy Disappeared is worth reading in its entirety or even better listening to him say it over.

Fountain opens with his statement of his creed:

I believe in God. Not that cosmic, intangible spirit-in-the-sky that Mama told me as a little boy “always was and always will be.” But the God who embraced me when Daddy disappeared from our lives — from my life at age four — the night police led him away from our front door, down the stairs in handcuffs.

Fountain goes on to explain how his life was difficult in the absence of his father, but he found real comfort in the belief in God he would ” know as father, as Abba — Daddy”. He then concludes by writing:

It wasn’t until many years later, standing over my father’s grave for a long overdue conversation, that my tears flowed. I told him about the man I had become. I told him about how much I wished he had been in my life. And I realized fully that in his absence, I had found another. Or that He — God, the Father, God, my Father — had found me.

In many ways the “God of our fathers” is the God who embraced Avraham, Yitzhak, and Yakov when their daddies disappeared, disappointed, or just fell short. If you have not figured it out already, the men’s group from above was actually my fanciful rendering of the conversation between our forefathers on the topic of their relationship with their fathers that I go through at the start of each and every Amidah.

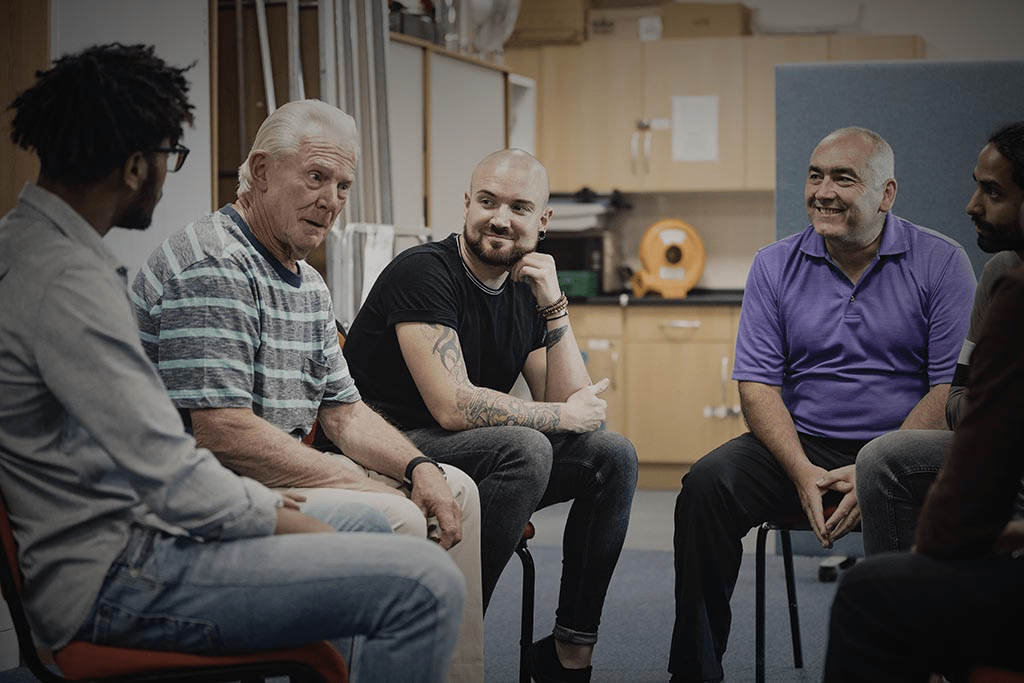

In a deep way this comes to explain where honoring your parents falls out in the 10 Commandments. Where the first 4 commandments are how we relate to God and the last 5 are how we relate to our neighbors. The relationship to our parents manifest in this 5th Commandment is the transition between our relationship to God and our relationship to society. For many of us how we related to our parents and God are interconnected. This makes me rethink my relationship with my parents. It also pushes me to be much more intentional as a father. And maybe for the sake of both I really should find a real life men’s group to join.

Leave a comment