When we think about the people we love in our lives, how close is too close? This is front of mind when it comes to my children. We are blessed to have one son off at college, another half way around the world on a gap year in Jerusalem, a 10th grade daughter who wants to differentiate , and our 4th grader complains that I hug her too much. I find myself constantly modulating to give each of them the space that they need, but not too much. And when I think about myself as a child, I ask myself, did my parents give me the right amount of distance when my parents were alive,? And now in their absence, I have turned my attention to my siblings. Since our parents’ passing we have been adjusting how we get along. In general, when we love people we want to be close to them, but we also know that people need our space. What is the right distance?

I was thinking about this question of distance in reading Vayera, this week’s Torah portion. Here we read about Hagar and Yishmael’s exile. We read:

And Abraham arose early in the morning, and he took bread and a leather pouch of water, and he gave [them] to Hagar, he placed [them] on her shoulder, and the child, and he sent her away; and she went and wandered in the desert of Be’er Sheba. And the water was depleted from the leather pouch, and she cast the child under one of the bushes. And she went and sat down מִנֶּ֗גֶד הַרְחֵק֙- from afar, at about the distance of two bowshots, for she said, “Let me not see the child’s death.” And she sat from afar, and she raised her voice and wept.(Genesis 21: 14-16)

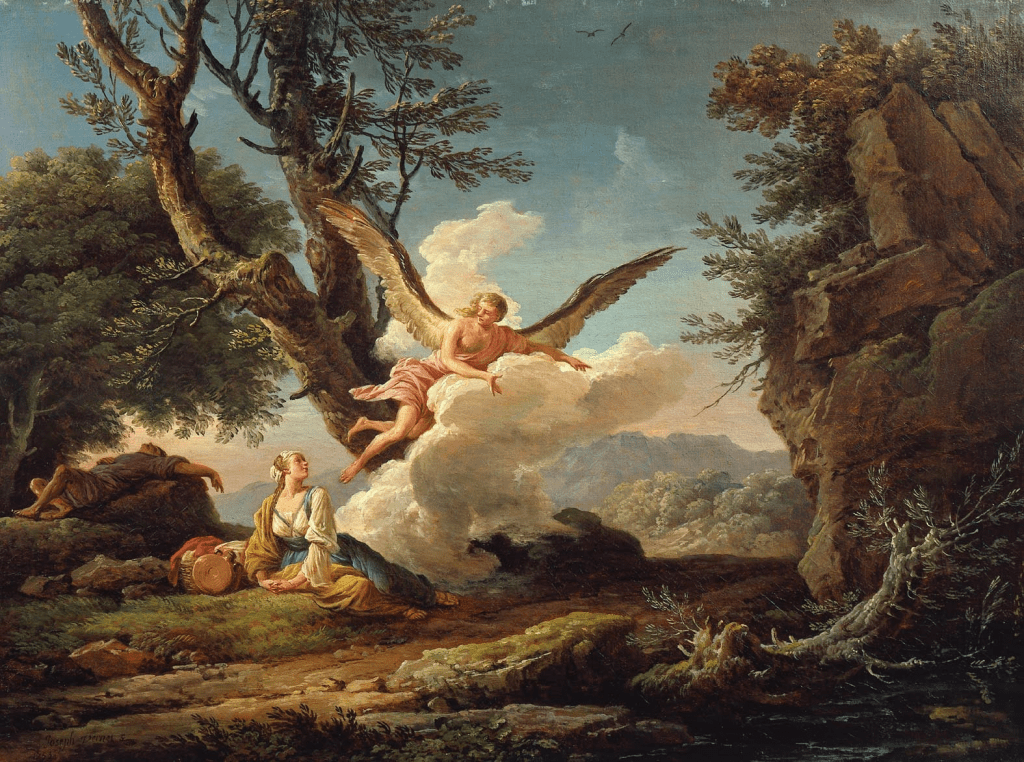

The simple reading of this situation is that Yishmael is about to die and Hagar could not bear to watch this happen to him. And at the same time this is her son and she could not just desert him. So, Hagar sits at a distance to watch, but not too close. Yishmael was about to perish from thirst when an angel “opened Hagar’s eyes” and showed her a well from which to give Yishmael water. It turns out that the water was there whole time. Yishmael is saved, but was it a miracle? While it ends well, it is a near tragedy that could have been averted. Looking at Hagar as a parent, the situation is sad and she seems a bit pathetic.

This “eye-opening” story about Hagar seems like a set up to show the juxtaposition with Avraham’s “eye-opening” experience with the Binding of Yitzhak. Did Avraham not see the ram there caught in the thicket? This might be true, but I do not want to skip over the Torah’s depiction of Hagar standing there at distance as her son was about to die of thirst in desert.

This image Hagar sitting at a certain distance watching of Yishmael seems to be foreshadowing another image of a young boy in peril being watched. When the children of Israel were slaves in Egypt a new King rose up who did not remember how Yosef had saved them. This new king looked to limit the risk of a slave uprising by killing all of the male children. As the story continues Moshe is born in hiding to two people from the tribe of Levi. But when they cannot keep the secret anymore, they resolve to make a Hail-Mary play to save the child by putting him in a basket to see what would happen to him. There we read:

And his sister stationed herself מֵרָחֹ֑ק- at a distance, to learn what would befall him. (Exodus 2:4)

Just as Hagar was watching Yishmael from afar, Miriam was hanging out in the bullrushes “at a distance” to see what would happen. Like Yishmael, Moshe is saved, but what do we see in their respective mother/sister hanging out at distance?

I like to think that Hagar and Miriam, were standing at the same distance, but with very different intentions. Where Hagar was being pathetic, Miriam seems almost ebullient and bursting onto the scene with Pharoah’s daughter. Where Hagar was deep in despair , Miriam is brimming with hope. Hagar was looking away while Miriam was looking out. Where Hagar was moving away from tragedy of the pending death of her son, Miriam was ready to jump on the opportunity of Pharoah’s daughter discovering her little brother. How might we understand these respective vectors? In the face of Moshe’s pending death, how could Miriam maintain her optimism?

Interestingly the juxtaposition of Hagar and Miriam here aligns to the thinking of the late Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik z’l. On Yom ha-Atzma’ut (Israel’s Independence Day), 1956, Soloveitchik delivered a public address at Yeshiva University entitled, “Kol Dodi Dofek; The Voice of My Beloved Knocks.” The address, which has become a classic of religious Zionist philosophy, enumerates and elaborates upon the instances of God’s tangible presence in the recent history of the Jewish people and the State of Israel. It also issues a clarion call to American Orthodoxy to embrace the State of Israel, and to commit itself and its resources to its development. There he outlines what he called the brit ye’ud (the covenant of destiny) and brit goral (the covenant of fate). Destiny is what we do. Fate is what happens to us. One is a code of action, halachah. The other is a form of imagination, the story we tell ourselves as to who we are and where we belong.

Hagar’s distance speaks of the covenant of fate. Hagar cannot run away or watch what is unfolding to her son Yishmael. Miriam’s distance speaks of the covenant of destiny. Miriam is eagerly looking out for the prophetic vision that will unfold for her brother Moshe and the salvation that will come from his life. While both distances speak of commitment and a bond, Miriam’s alone speaks of a hope for the future.

Or perhaps I am being too judgative (thank you Yishama for this word) of Hagar. As I often quote, Brené Brown brilliantly writes:

It got me thinking about the people I’ve been struggling with and judging. I asked myself – are they doing the best they can with the tools that they have? (Rising Strong)

Do we think that Hagar was doing her best? Brown says about the people who are doing their best:

They were slow to answer and seemed almost apologetic, as if they had tried to persuade themselves otherwise, but just couldn’t give up on humanity. They were also careful to explain that it didn’t mean that people can’t grow or change. Still, at any given time, they figured, people are normally doing the best they can with the tools they have.

…Every participant who answered “yes” was in the [research] group of people who I had identified as wholehearted— people who are willing to be vulnerable and who believe in their self-worth. They offered examples of situations where they made mistakes or didn’t show up as their best selves, but rather than pointing out how they could and should have done better, they explained that, while falling short, their intentions were good and they were trying. (Rising Strong)

It is possible that Hagar just has crappy tools compared to Miriam?

Looking back on this past year, the Jewish people had experiences a metric ton of crap. Look forward to this coming year, what will happen? How will we show up? Are we showing up wholehearted when it comes to Israel and Palestine? Are we at the right “distance”? Or more importantly what is our vector? Are we looking away as we are fated for more pain and suffering or are we leaning into our destiny and scanning the horizon for a better and brighter future? The secret to our resilience as people is our picking Miriam’s vantage point over Hagar’s. We pick destiny and salvation over a fate and suffering every time. Our hope is born out of our vigilance and willingness to be like Miriam and jump at any opportunity that floats our way. Hope is the foundational Jewish tool that has allowed us to survive throughout history.

Going back to the original question, what is the right distance with those we love? We need to stand close, but not too close. From this vantage point need to trust that everyone is doing the best got with the tools they got. And if we do not trust ourselves, it is time to invest in a better tools. We need to hold space for them, but even more so we need to hold hope.

- See related post- The Right Distance: Hagar and Miriam

Leave a comment