Last year a friend, who is congregational Rabbi, posted on Facebook that his favorite Tallis got a ripped and he did not know what to do. To him this was tragic.

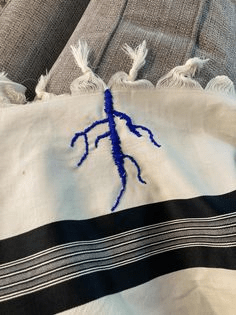

It is interesting because I had the same problem, but I saw it an an opportunity. Here is the picture of my handy work that I sent him.

It is interesting that we were literately cut of the same cloth, but saw things very differently. In trying to explain my my mindset I realized I had done my own version of Kintsugi

Kintsugi (金継ぎ, “golden joinery”), also known as kintsukuroi (金繕い, “golden repair”), is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. As a philosophy, Kintsugi treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise. Instead of trying to hide what is broken you adorn it and make that beautiful.

As a philosophy, kintsugi is similar to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, an embracing of the flawed or imperfect. Japanese aesthetics values marks of wear from the use of an object. This can be seen as a rationale for keeping an object around even after it has broken; it can also be understood as a justification of kintsugi itself, highlighting cracks and repairs as events in the life of an object, rather than allowing its service to end at the time of its damage or breakage. Collectors became so enamored of the new art that some were accused of deliberately smashing valuable pottery so it could be repaired with the gold seams of kintsugi.

I was thinking about Kintsugi and my fixed Tallit now in preparation for Shabbat Bereishit, when we read about the creation of the world. In order to explain the the basic problem of diverseness and multiplicity in Creation as well as the origin of evil the Kabbalists and then the Chasidim after them taught this idea of “Shevirat haKeilim– The shattering of the vessels”. The concept of Shevirat haKeilim is linked to the Midrashic account of the building and destruction of the primordial worlds (Bereishit Rabba 3:7, 9:1) and is a central component in the Arizal’s system of Kabbala.

Here’s the concise narrative that describes a cosmic catastrophe that occurred during the process of Creation:

- Tzimtzum (Contraction): In the beginning, the infinite Divine light (Ein Sof) contracted itself to create a vacant space for the universe to exist.

- Creation of the Vessels (Keilim): Into this space, God poured His emanating light in ten successive stages, corresponding to the ten Sefirot (Divine emanations/attributes). This light was initially contained within vessels (Keilim).

- The Catastrophe (Shevirah): The first three vessels, which housed the highest, most refined lights (Wisdom, Understanding, and Knowledge), were strong enough to contain their light. However, the subsequent six vessels, which housed the lower, more potent lights (representing qualities like kindness, judgment, and beauty), were too fragile. They shattered under the intensity of the Divine influx.

- The Resulting Chaos:

- The greater portion of the light ascended back to its source.

- “Shards” or “Vessels” (Klippot): Fragments of the shattered vessels (the Klippot, or “shells”) fell into the newly created space, forming the material world. These fragments contain the sparks of Divine light (Nitzotzot) that were trapped when the vessels broke.

- The World of Correction (Tikkun): Our physical, imperfect world is the result of this initial shattering, containing a mix of pure Divine light and the dark, chaotic shards (the source of evil and impurity).

The narrative’s central theological purpose is to set the stage for the concept of Tikkun Olam (Repairing the World). The ultimate mission of humanity, particularly the Jewish people, is to perform mitzvot (commandments) and engage in ethical actions to liberate the trapped Divine sparks from the Klippot and restore the universe to its intended perfect state, thereby completing the cosmic process that began with the Shevirah. It seems that this idea of Tikkun Olam as a means of putting the pieces of the broken world back together is just another form of Kintsugi.

Looking around and seeing how absolutely broken the world is it seems that the work of fixing the world might be too hard for us. How do we make sense of the world? How do we make sense of a Creator? How do we make sense of our role in this world? Rabbi Shai Held wisely said that all contemporary theology is kintsugi.

The Rebbe, Rav Menachem Mendel Schneerson, said, “If you see what needs to be repaired and know how to repair it, then you have found a piece of the world that God has left for you to perfect. But if you only see what is wrong and what is ugly, then it is you yourself that needs repair.” It is enough work for us to try to fix the world without trying to curate some false pretense of perfection. What would it look like if we celebrated or even gilded the damage? The invitation for partnership is clear, we have a lot of work to do.

Leave a comment