In Bo, this week’s Torah portion, we read about the rest of the Ten Plagues. There at the nadir with the killing of the first born we read:

And there shall be a loud cry in all the land of Egypt, such as has never been or will ever be again; but not a dog shall move its tongue- snarl at any of the Israelites, at human or animal—in order that you may know that GOD makes a distinction between Egypt and Israel. ( Exodus 11:6-7)

The Bible describes a “great cry” of sorrow across Egypt due to the death of the firstborn, but specifies that not even a dog would “move its tongue” against the Israelites. This “great cry” makes sense. One can only imagine the pure anguish at the prospects of losing a child. What is the deal with the dog’s silence? The people were so shaken that when they cried out they freaked out their pets. Why is this metric of the impact of this moment in Egypt?

This question is compounded by an interesting Gemara that reads:

The Sages taught: If the dogs in a certain place are crying for no reason, it is a sign that they feel the Angel of Death has come to the city. If the dogs are playing, it is a sign that they feel that Elijah the prophet has come to the city. These matters apply only if there is no female dog among them. If there is a female dog nearby, their crying or playing is likely due to her presence. (Baba Kama 60b )

You would have assume from this that the male dogs would have been crying due to the presence of the the Angel of Death. This is easy to resolve. In this case they had a reason. Either their silence was a response to the people’s crying or the presence female dogs. This itself projects an interesting notion of gender. This suggests that in the Rabbinic mind is there a projection of a gendered anthropopathism here. That the female dogs did not cry out of empathy for the Egyptian mother’s pain. Dogs are truly man’s best friend.

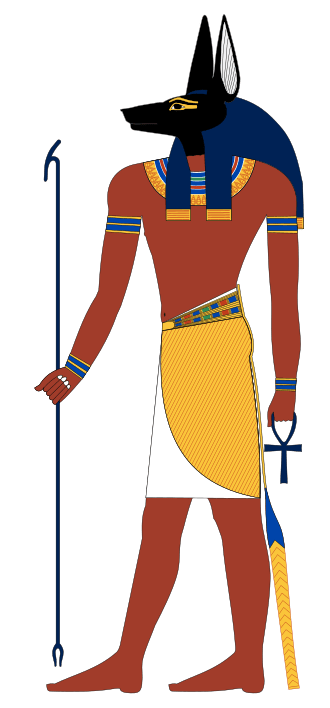

And yet there is a completely alternative reading to all of this. In Egyptian mythology Anubis is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the “Weighing of the Heart”, in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon; however, few major myths involved him.

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.

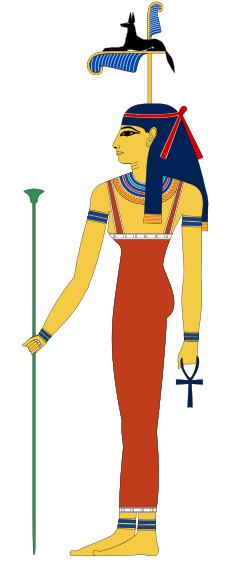

Anubis’s female counterpart is Anput. She is also depicted as a woman, with a headdress showing a jackal recumbent upon a feather, as seen in the statue of the divine triad of Hathor, Menkaure, and Anput. She is occasionally depicted with the body of a woman and the head of a jackal, but this is very rare.

As the consort of Anubis, Anput is a goddess of the dead, presiding over funerals and mummification. Additionally, she is a goddess of protection and also represented in relation to the desert, which was the realm of the dead for Ancient Egyptians. Unlike Anubis, Anput does not have a prominent role in Egyptian mythology, but she is thought to watch over the body of the god of the afterlife, Osiris, assuming the role of his protector for the duration of his death.

For me many of these ideas come together with the image of Anput’s headdress showing a jackal recumbent upon a feather. This image of a silent dog ushering the dead to the afterlife resonates with the image of the silent dogs there in Egypt in the wake of the 10th plagues. Like a record skipping at a party when things are about to go sideways, the absence of the dogs barking speaks to severity of the moment. It also points to some cosmic notion of empathy. It is heart warming to imagine the long history and connection between human’s and our canine companions. This silences and lack of dogs growling at this moment might also be a nod to Anput.

(And all of this might offer us some depth to Vayadom Aharon- Aaron’s silence upon the news of the death of his two sons Nadav and Avihu (Leviticus 10:3)- but that is for another time. )

Leave a comment